Digital Distributors: The Supermarkets of the Web

It's hard to ignore the strong force of digital distributors on the open web. In a previous post, I focused on three different scenarios for the future of the open web. In two of the three scenarios, the digital distributors are the primary way for people to discover news, giving them an extraordinary amount of control.

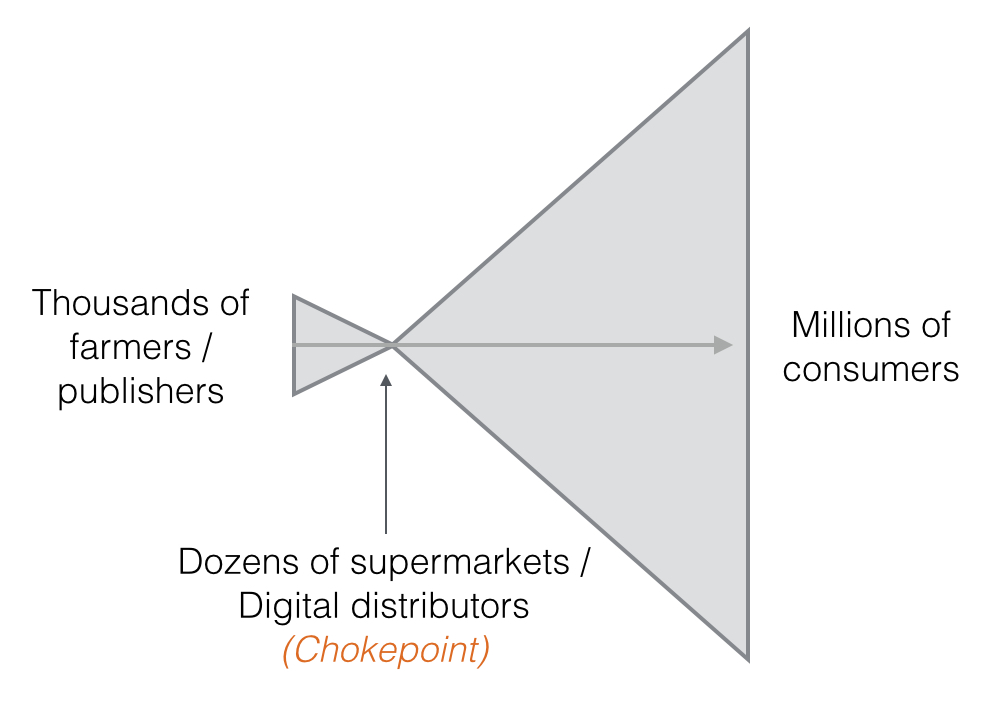

When a small number of intermediary distributors get between producers and consumers, history shows us we have to worry — and brace ourselves for big industry-wide changes. A similar supply chain disruption has happened in the food industry, where distributors (supermarkets) changed the balance of power and control for producers (farmers). There are a few key lessons we can take from the food industry's history and apply them to the world of the web.

Historical lessons from the food industry

When food producers and farmers learned that selling directly to consumers had limited reach, trading posts emerged and began selling farmers' products more than their own. As early as the 14th century, these trading posts turned into general stores, and in the 18th century, supermarkets and large-scale grocery stores continued that trend in retailing. The adoption of supermarkets was customer-driven; customers benefit from being able to buy all their food and household products in a single store. Today, it is certainly hard to imagine going to a dozen different speciality stores to buy everything for your day-to-day needs.

But as a result, very few farmers sell straight to consumers, and a relatively small amount of supermarkets stand between thousands of suppliers and millions of consumers. The supermarkets have most of the power; they control how products are displayed, and which ones gain prominent placement on shelves. They have been accused of squeezing prices to farmers, forcing many out of business. Supermarkets can also sell products at lower prices than traditional corner shops, leading to smaller grocery stores closing.

In the web's case, digital distributors are the grocery stores and farmers are content producers. Just like supermarket consumers, web users are flocking to the convenience and relevance of digital distributors.

Control of experience

Web developers and designers devote a tremendous amount of time and attention to creating beautiful experiences on their websites. One of my favorites was the Sochi Olympics interactive stories that The New York Times created.

That type of experience is currently lost on digital distributors where everything looks the same. Much like a food distributor's products are branded on the shelves of a supermarket to stand out, publishers need clear ways to distinguish their brands on the "shelves" of various digital distribution platforms.

While standards like RSS and Atom have been extended to include more functionality (e.g. Flipboard feeds), there is still a long way to go to support rich, interactive experiences within digital distributors. As an industry, we have to develop and deploy richer standards to "transport" our brand identity and user experience from the producer to digital distributor. I suspect that when Apple unveils its Apple News Format, it will come with more advanced features, forcing others like Flipboard to follow suit.

Control of access / competition

In China, WeChat is a digital distributor of different services with more than 0.5 billion active users. Recently, WeChat blocked the use of Uber. The blocking comes shortly after Tencent, WeChat's parent company, invested in rival domestic car services provider Didi Kuaidi. The shutdown of Uber is an example of how digital distributors can use their market power to favor their own businesses and undermine competitors. In the food industry, supermarkets have realized that it is more profitable to exclude independent brands in favor of launching their own launching grocery brands.

Control of curation

Digital distributors have an enormous amount of power through their ability to manipulate curation algorithms. This type of control is not only bad for the content producers, but could be bad for society as a whole. A recent study found that the effects of search engine manipulation could pose a threat to democracy. In fact, Google rankings may have been a deciding factor in the 2014 elections in India, one of the largest elections in the world. To quote the study's author: search rankings could boost the proportion of people favoring any candidate by more than 20 percent — more than 60 percent in some demographic groups

. By manipulating its search results, Google could decide the U.S. presidential election. Given that Google keeps its curation algorithms secret, we don't know if we are being manipulated or not.

Control of monetization

Finally, a last major fear is control of monetization. Like supermarkets, digital distributors have a lot of control over pricing. Individual web publishers must maintain their high quality standards to keep consumers demanding their work. Then, there is some degree of leverage to work into the business model negotiation with digital distributors. For example, perhaps The New York Times could offer a limited-run exclusive within a distribution platform like Facebook's Instant Articles or Flipboard.

I'm also interested to see what shapes up with Apple's content blocking in iOS9. I believe that as an unexpected consequence, content blocking will place even more power and control over monetization into the hands of digital distributors, as publishers become less capable of monetizing their own sites.

— Dries Buytaert

Dries Buytaert is an Open Source advocate and technology executive. More than 10,000 people are subscribed to his blog. Sign up to have new posts emailed to you or subscribe using RSS. Write to Dries Buytaert at dries@buytaert.net.