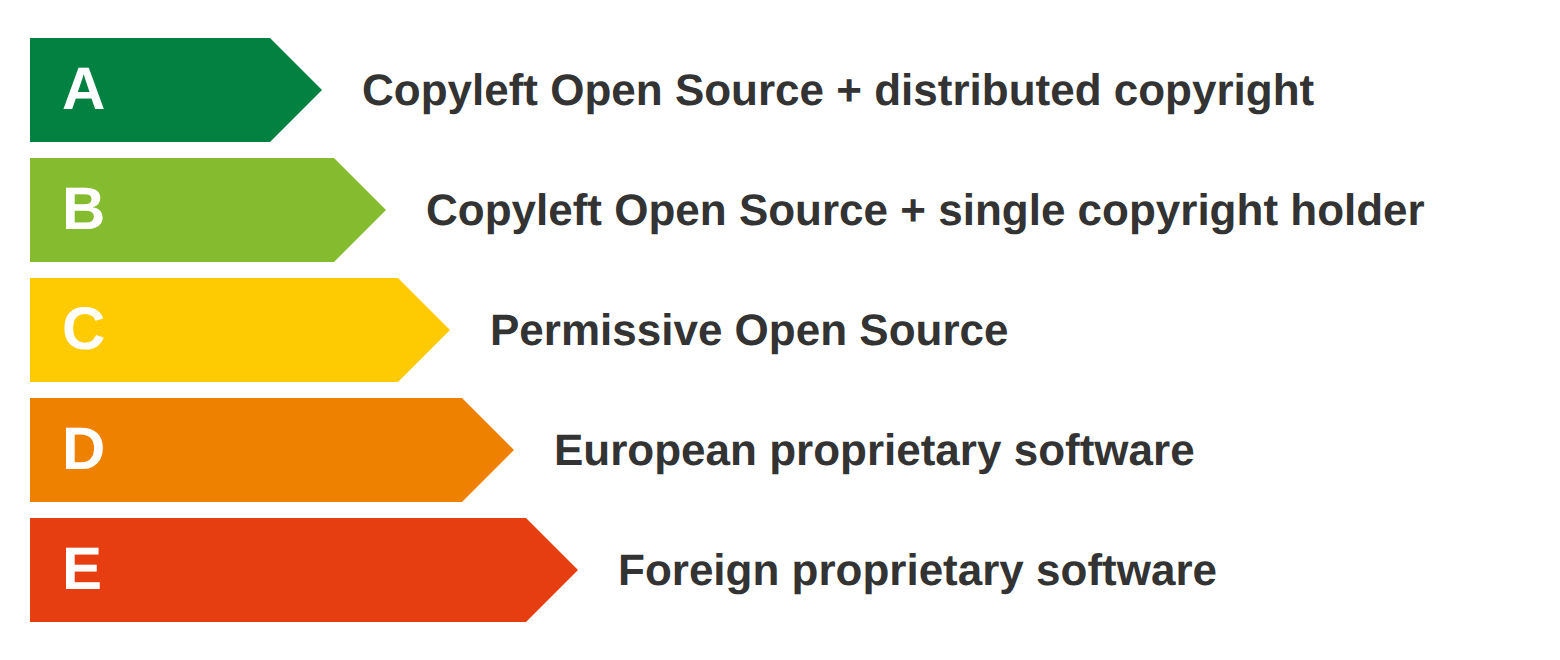

The Software Sovereignty Scale

Digital sovereignty depends less on where software comes from and more on who controls it. This post introduces a scale showing which technologies can never be taken away.

"Buy European" is becoming Europe's rallying cry for digital sovereignty. The logic is intuitive: if you want independence from American technology, buy from European companies instead.

However, I think "Buy European" gets one thing right and one thing wrong. It's right that Europe benefits from a stronger technology industry. But buying European does not guarantee sovereignty.

Sovereignty is not about where a company is headquartered or where software was originally written. It is about whether you retain "freedom of action" over the technology you depend on, even if the vendor changes strategy, gets acquired, or disappears.

The right question to ask about any technology: if conditions change, do you retain the freedom to keep using, modifying, and maintaining this software?

When evaluating sovereignty, it is not enough to ask how much control you have today. You also need to ask how much of that control is structurally protected, built into the legal and community foundations, so it can't be taken away tomorrow.

The proposed scale measures structural protection. It is not a ranking of openness, nor does it capture every dimension of sovereignty. The scale also does not imply that one license is always better than another.

The most important distinction in the scale is between Open Source and proprietary. All three green grades give you freedom of action: the right to use, modify, and maintain the software independently, forever. The differences between A, B, and C reflect how structurally protected that freedom is against acquisition, relicensing, or ecosystem shift. They also determine how much you risk being left behind if the project's direction changes.

I used five levels, modeled on Europe's familiar A-through-E labels for energy efficiency and food nutrition, from structurally sovereign to fully dependent. Frameworks like the European Commission's Cloud Sovereignty Framework do not yet make these structural distinctions. This scale aims to improve on what exists and is used today, and I expect it to improve further through scrutiny and feedback.

| Type | Can someone take it away? | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Copyleft + no relicensing risk | No. The code cannot be relicensed, and all derivatives must be Open Source forever. | Linux, Drupal, WordPress |

| B | Copyleft + relicensing risk | No. All derivatives must be Open Source. But future versions can be relicensed if copyright is concentrated. | MySQL → MariaDB |

| C | Permissive Open Source | No. But the license allows proprietary derivatives that can shift value away from the open project. | Redis (relicensed), Valkey (fork) |

| D | European proprietary software | Yes. A single acquisition transfers all control. Funding can disappear. You're a customer, not a stakeholder. | Skype |

| E | Foreign proprietary software | Already taken. Subject to the vendor's pricing, roadmap, and their government's jurisdiction. You're a customer, not a stakeholder. | Microsoft, Oracle, Salesforce |

Jurisdictional obligations change with ownership

At the bottom, grade E, is foreign proprietary software: no source code, no right to modify, and no alternative if the vendor changes terms. Your vendor is subject to its home government's jurisdiction, and by extension, so is your data.

Grade D is European proprietary software, which is where "Buy European" usually comes in. It has real benefits: European jurisdiction, GDPR alignment, local accountability, and it keeps investment circulating in the European ecosystem. As someone who has started companies and invests in startups, I want more technology companies to succeed, not fewer. But "European" can be a temporary property of a company: it can change with a single board meeting.

Skype was founded by a Swede and a Dane, built by Estonian engineers, and headquartered in Luxembourg. eBay acquired it in 2005, and Microsoft acquired it in 2011. The eBay transaction turned a world-leading European technology into an American one, and it was cemented with the Microsoft deal.

So ownership and jurisdiction matter, but they're not enough. A European company can be acquired tomorrow. Open Source offers something more important: it separates the code from any single company or country.

Not all Open Source is equally sovereign

Open Source is what makes real sovereignty possible. At the same time, Open Source sovereignty exists on a spectrum. The level of protection comes down to two legal levers: the license itself, and the copyright ownership, which determines who has the power to change the license.

Grade C is Open Source under a permissive license like BSD, MIT, or Apache. You can view the code and fork it if needed, but the license does not require improvements to remain open. A company can take the code, build on it, and release a proprietary version.

The relicensing risk applies mainly to single-vendor projects. When a permissive project is hosted at a vendor-neutral foundation like Apache or Eclipse, the foundation holds the governance and the relicensing risk is minimized. The relicensing risk in grade C mainly comes from corporate control, not from the license itself.

Redis shows how this dynamic unfolds. It was Open Source under a BSD license for fifteen years. In March 2024, Redis Ltd. relicensed it under restrictive terms that the Open Source Initiative does not approve as Open Source.

Fortunately, the community forked the last open version as Valkey, and Valkey is thriving. That is the strength of permissive Open Source: you can escape when terms change. Governments were fortunate Redis was forked, but the structural risk remains, and in many cases end users are not so lucky. They are left maintaining the software themselves, which can be costly and unsustainable.

Grade B is Open Source under a copyleft license like the GPL. Copyleft adds a protection permissive licenses lack: any derivative of released code must also remain Open Source. For policymakers, this is a meaningful upgrade.

This is the level that saved MySQL. MySQL AB, the Swedish company behind MySQL, released it under the GPL, so when Oracle acquired MySQL through the Sun Microsystems deal, the GPL ensured the code remained open. Michael Widenius, MySQL's original creator, took the code and built MariaDB. Oracle got the brand, but the world kept the code.

And because MariaDB inherited MySQL's GPL license, it must stay open too. No future acquirer can make MariaDB proprietary. That is the difference between copyleft and a permissive license: copyleft lets someone fork and forces all forks to stay open.

But grade B still has one limitation. When copyright is concentrated, the holder can release future versions under a different license. The existing code is protected by the GPL, but the project's future direction depends on who holds the copyright and how they are governed. A vendor-neutral foundation holding the copyright carries far less risk than a single company.

Some projects amplify this risk by requiring contributors to sign a Contributor License Agreement, or CLA, which grants the project owner the right to relicense contributed code. Elasticsearch, founded in Amsterdam, used its CLA in 2021 to relicense from Apache 2.0 to a non-open-source license, despite having over 1,500 contributors.

Finally, grade A is copyleft Open Source with no relicensing risk. This typically happens when copyright is governed by a neutral foundation, or when hundreds or thousands of contributors each own their portion of the code. In that case, relicensing would require consent from every contributor, and any refusal would force the project to rewrite that code from scratch. The more distributed the ownership, the harder relicensing becomes.

Drupal has had contributions from tens of thousands of people across 25 years, which makes relicensing structurally impossible. No acquisition, no board vote, no change in strategy can take these projects away from the people who build and depend on them. Copyleft projects with fewer independent contributors can be easier to relicense. Drupal's code is structurally sovereign by design.

Sovereignty is a long-term commitment

Moving from E to D is progress. Moving from D to C is what really matters. Above C, the scale highlights smaller but still important tradeoffs, so when governments choose a lower grade, they do so knowingly rather than unknowingly.

An Open Source project that loses important funding often needs investment to remain viable. But unlike acquisition or relicensing, funding risk is largely within the EU's control through government procurement and public investment.

Recommendation for the European Commission

Sovereignty involves many things: data location, supply chains, technical talent, and standards. Licensing and copyright form the structural foundation because they determine whether legal independence is even possible.

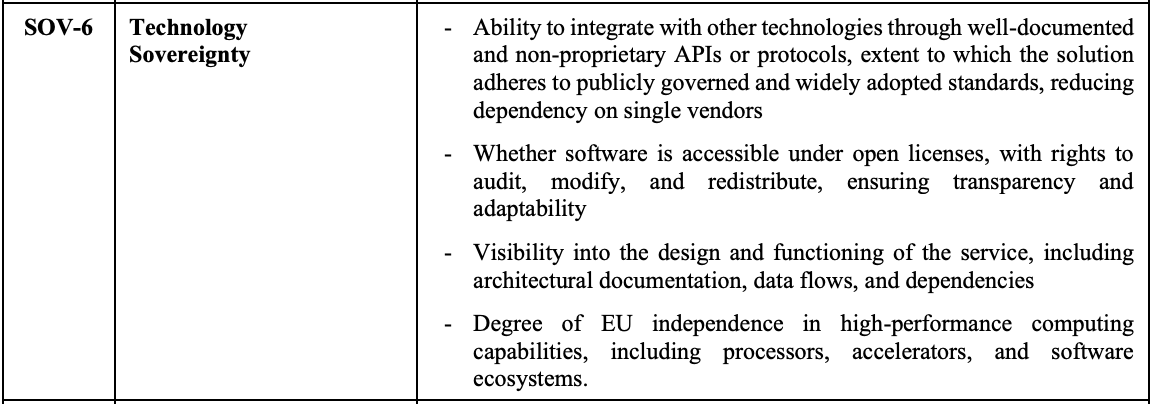

The European Commission's Cloud Sovereignty Framework reflects this broader view. It evaluates cloud software across eight sovereignty objectives, each scored and weighted into a composite sovereignty score. Technology Sovereignty (SOV-6), the objective that covers open licensing, accounts for 15% of that composite. Within it, open licensing is one contributing factor among four, alongside open standards, architectural transparency, and EU computing independence.

This dramatically underweights what matters most: Open Source. Open standards, transparency, and computing independence are capabilities that proprietary software can also provide. They can change if a vendor is acquired or shifts strategy.

Open licensing creates permanent, irrevocable rights to use and modify the software regardless of what happens to the vendor. It is the only contributing factor within Technology Sovereignty (SOV-6) that makes sovereignty structural rather than situational, yet the framework does not distinguish it from the others. Nor does it recognize that open licensing underpins the other sovereignty objectives: operational independence, supply chain resilience, and jurisdictional flexibility all depend on whether you have the right to move, modify, and maintain the software. I would encourage the Commission to strengthen its Technology Sovereignty objective in three ways:

-

Give open licensing significantly more weight in the sovereignty score. Open licensing is not comparable to the other three contributing factors in Technology Sovereignty. It is the only one that creates permanent, irrevocable rights. The framework should reflect that.

-

Distinguish between license types. Permissive licenses (BSD, MIT, Apache) place no obligation on derivatives to remain open. Copyleft licenses (GPL, AGPL) require derivative works to be released under the same open terms.

-

Assess copyright concentration and relicensing risk. Not all projects carry equal risk of relicensing. A project controlled by a single company can be relicensed. A project with distributed copyright ownership, or one governed by a vendor-neutral foundation, is far more resistant to relicensing. This is the difference between a revocable and an irrevocable commitment to openness.

Open licensing is not one consideration among many. It is the foundation that makes all other sovereignty objectives durable. I think European procurement policy should weight it accordingly. The Software Sovereignty Scale can help: when a government selects a content management system for its public websites or a database for its national health records, it should know the structural sovereignty grade of the technology it depends on.

For critical software, the question is simple: how easy is it for someone to take the software away from us?

Special thanks to Sachiko Muto and Bert Boerland for their review and contributions to this blog post.

—

PS: Follow the discussion on LinkedIn.